These days, I try to not watch much television. More than 90% is crap. Even when it’s great, the opportunity cost is usually greater.

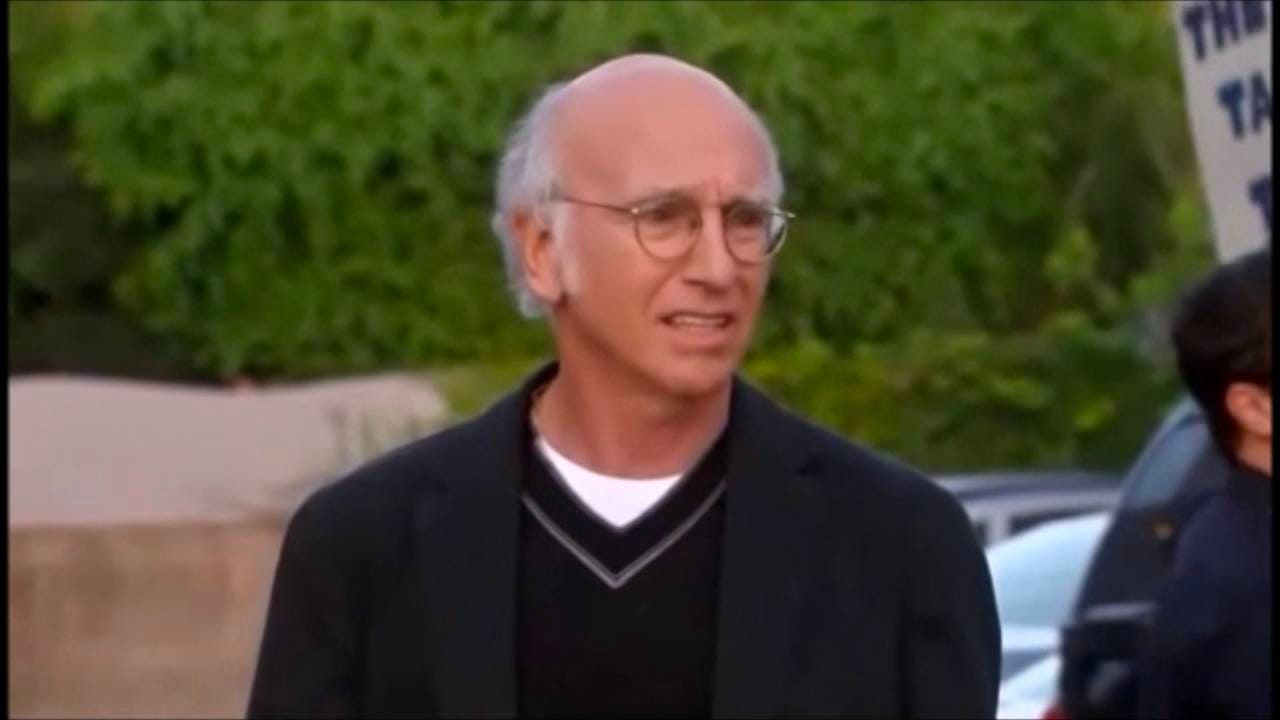

Inexplicably, during my peak television viewing as a university student, I never watched Curb Your Enthusiasm. I’m now barely half way through and immediately recognise it sits comfortably alongside The Sopranos and Breaking Bad1.

But what makes Curb so good?

The first reason is the most simple: Larry David is funny. Very funny. Comedy generates immediate feedback: We laugh or we don’t2. And Larry has us doing a lot of the former.

Secondly, the show uses a lot of improvisation. I tend to agree with Keith Johnstone that most people should try improv. It teaches comfort in vulnerability, enables self-directed learning, and unlocks all the deep philosophical secrets of the universe3.

Thirdly, Leon might be the best character to be introduced after season one. Seriously, does anyone come close4?

But the main reason for Curb’s excellence, the reason I’m writing about it, is that it subverts of The Absurd5.

The first to write about The Absurd was everyone's second favorite post-war French smoker come existential novelist come philosopher: Albert Camus, in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus.

Like many, my introduction to Camus was his novella The Stranger. Let’s put aside its literary merit displayed by its arresting opening line and its ability to send the reader to an unbearably hot French colonial Algeria. As a work of philosophy, it’s overrated.

What can I say? I’m just not totally sold on Camus's view that the only reason Merseault was sentenced to death was his refusal to “play the game”. Call me a philistine, but Merseault’s behavior seems relevant when considering his punishment. Specifically, I would hope that jury members noticed that he’s a dangerous sociopath who views Arab life as cheap, holds no regrets for murder, and displays no feelings6.

In fact, the book is best read as an accurate description of a sociopath: A man who lacks normal feelings and conscience.

But I digress.

Camus’ essay on Sisyphus is where he drills down on the absurd. You know, the story of Sisiphus slowly pushing a boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down again. Pushing it back up. It rolls back down. Push up. Rolls down. Up. Down. Like some awful Katy Perry lyric.

We all agree this is some kind of groundhog day torture scenario. But then we think about it, in the middle of our weekly grocery shop, and realize that this story feels a little familiar and maybe it’s just this big old metaphor for life.

And then when we get our notification reminding us that we’re late for our daily atomic habit we diligently committed to last month. It all comes to an apotheosis and we realize that maybe, just maybe, everything might be meaningless.

We don’t quite Woody-Allen-character-in-Hannah-and Her-Sisters-level freak out, but we do have doubts. The question arises: does any of this matter? The universe, for all its amazing intelligibility, stubbornly remains silent on this question7.

I suppose there’s a little absurdity in that.

The Philosopher Thomas Nagel has his own take. He agrees that life is absurd. But it’s not due to a disconnect between our search for meaning and the universe’s refusal to provide it. Rather, there’s a disconnect within us.

Life is absurd due to a combination of two aspects: (1) we devote energy and seriousness to our decisions, goals, and daily tasks; and (2) we are able to take a step back to acknowledge that this might be ultimately arbitrary. The absurdity lies in the fact that we do not resolve these doubts but invariably go back to treating our beliefs and actions, from our tofu dinners to our TODO lists, with total seriousness.

Even in writing this essay, moments after reflecting on the potentiality of total arbitrariness, I am committed to making it as coherent, persuasive and clear as possible. I couldn’t be more cognizant of the absurd and I still can’t avoid it.

Larry David, through his character in Curb Your Enthusiasm, subverts this.

It’s not that he manages to avoid the seriousness that plagues us. Quite the contrary. He embraces it. Larry is totally committed to rectifying any perceived injustice that causes the slightest inconvenience.

What Larry manages to avoid is the doubts. He isn’t concerned that life is arbitrary. There’s cosmic injustice to put right. There’s no traversing down the tower of turtles to find that there’s no final justification.

Any slight norm transgression becomes universally significant. Everything else is beside the point.

He’ll lose a TV deal before agreeing to an unfair share of commutes to meetings.

He’ll risk the education of his best friend’s daughter to uphold the norms on how many free samples are acceptable at an ice cream parlor.

And in the most quintessentially Larry moment, after a Herculean effort to salvage his marriage, he derails his last chance in a single moment by not dropping his insistence on his wife and others acknowledging that it wasn’t him who left a stain ring on a coffee table.

As psychologist Dave Pizarro says: Principled Neurosis.

Can this really be an escape from the absurd? I asked myself this after recently finishing Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Love and work aside, what if instead we lived like Larry David? Is it that simple?

How hard would it be? It’s not like Larry never has a point. In fact, in many cases, his underlying point is totally right.

What if instead of acquiescing to the way my girlfriend was preparing chicken sandwiches for lunch yesterday, I stood my ground: Blue Plates mayonnaise simply will not do8. That brand doesn't even deserve to be selling the same product as Hellman’s Best Foods. Why is Blue Plates even in the house? Leave no room to doubting my conviction and potential overreaction and head to the supermarket.

What would have happened? Well we would have been late for the game night with our friends that afternoon. But we might have avoided the absurd (and Blue Plates).

What if I continued to act this way once we arrived at the games night: Keep speaking truth to power. There was this guy there that no one knew very well (he was the new boyfriend of one of the girls). During Scattergories, he kept submitting questionable answers. Which is forgivable. But it was the monumental combination of their dubiousness, his lack of awareness of this fact, and his pedantry on other people’s turns.

I didn’t say anything because I hardly knew the guy. But what would Larry do? He’d stick up for what’s right: “Mountains” is not a valid answer for “things you find on a sports’ field”. I don’t care if he’s been to Switzerland. We already allowed his dubious “pen” for “things that are orange”.

He’s violating the spirit of the game and now he’s winning. We can accept others winning, but not the violation of the spirit.

The spirit must be respected.

What if I’d respected the spirit? If I’d pushed back with passionate intensity? Well, we may have not been invited back. Would that have been worth it? Losing friends on the one hand, but, to paraphrase Goodman in Big Lebowski, at least I’d have been following an ethic.

My guess is that, try as I might, I wouldn’t have been able to avoid the absurd. As Nagel states, the realization of life’s potential arbitrariness is inescapable. It is hard not to doubt the potentiality that Scattergories etiquette might not be all that important in the scheme of things. It’s probably not worth being a dick over.

Larry is a rare breed. A paragon of Nietzsche's Übermensch. Think Chigurgh from No Country for Old Men but without the 1970s layered bob, the cattle bolt stunter, and the serial killer vibe. They both have principles: Strong convictions and no concerns about the endless quest for meaning.

For the rest of us, the exaggerated devotion towards trivial goals that Larry displays in Curb highlights the absurdity of the seriousness that we treat ours.

And maybe that’s OK.

Instead of fighting the absurd, it may be best to follow the advice of Morty: Everybody is going to die. Come watch TV.

I ended up checking some “top 50” lists and noticed two things: good tv isn’t made anymore and these lists offer no surprises.

Although, interestingly, most laughter is not due to humor. Laughter expert Robert Provine estimates that humor accounts for about 10-20% of laughter.

Some contenders: Marlo from The Wire, Saul from Breaking Bad, Danny Devito from Always Sunny, Lionel Hutz and Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons, and Oberon and Ramsey from Game of Thrones. I'd still give it to Leon.

The Very Bad Wizards podcast pointed this connection out during a riff in their episode on Nagel’s The Absurd.

I’m aware that nihilism/absurdity is also a theme in The Stranger. Who’s to say that Merseault’s cold-blooded murder is wrong? People will be famiiar with this moral problem if they’ve attended a Phil 101 tutorial where that one smart but somewhat unaware first year kid spends the entire class arguing with the tutor that it’s not necessarily wrong to murder everybody in the room right this very minute.

Adequate appreciation of condiments reminds me of David Foster Wallace’s hypothetical Lynchian scenario where two murder investigators discuss the merits of Jiff vs Skippy peanut butter while standing over a bloody female corpse who was murdered by her husband [i]. The husband was fed up with his wife’s inability to buy the correct peanut butter. So he murdered her. Lynch touched the absurd.

[8i] Doing a footnote to a footnote feels forgivable just this once since it’s about David Foster Wallace. When rereading the free version of DFW’s Lynch essay to provide a link I noticed that the editors cut out the story with the peanut butters which is arguably the best section. Life is absurd indeed.

This is a great essay, I made the comparison between Sisyphus and Larry and you are the only person who has done the same