Infinite Double Binds

Another theme in Infinite Jest (No major plot spoilers)

As everyone around me knows, I finished Infinite Jest recently. It’s about many things: Addiction, loneliness, tennis, family, absurdism.

I previously wrote about how it’s about recursion. It’s also about double binds.

Double binds are situations where you’re confronted with two conflicting demands but both options are bad.

Think of Groucho Marx’s joke about not wanting to belong to any club that will have him as a member. Damned to a life of loneliness or a member of subpar group.

Life is full of double binds

David Foster Wallace thinks life is made up of double binds. He wonders if the stuff that’s most interesting or most true involves them. Namely, set ups that are mutually exclusive but the trade offs involved in either of them seem unacceptable.

For example, our culture places a lot of value on achievement: But how do we invest enough of ourselves to achieve something while retaining a sense of self that is separated from that achievement?

Wallace even describes the difficulty in writing Infinite Jest. The book is long but it’s structured to be read more than once (it’s recursive). So it has to be fun enough for readers to be willing to pick it up again. But it has to be fun in a way that isn’t reductive or pandering or show-offy as that would be falling victim to the risks that the book is warning against.

In an unrelated essay on Dostoevsky, Wallace wonders:

Am I a good person? Deep down, do I even really want to be a good person, or do I only want to seem like a good person so that people (including myself) will approve of me? Is there a difference? How do I ever actually know whether I’m bullshitting myself, morally speaking?

Can we do good without being motivated by status? If we somehow transcend the all-too-human concern of worrying about how we look to others, then this very act of not caring becomes an honest signal of integrity which is genuinely impressive. We’re back to impressing others (which we enjoy).

Consider mental health: The cruel irony is that the best stuff you can be doing to improve things is the stuff that’s hardest to do when you’re feeling depressed. At one point, one of the characters, Avril Incandenza, describes to her youngest son Mario that the paradox of sadness is that it stops expression and imprisons you which is itself sad and painful.

Also in relationships: If you are considering a break up, both options may seem unbearable: You have to weigh up an inability to function alone vs a dysfunctional, unhappy relationship. If kids are involved, the double bind is stronger.

Double binds in Infinite Jest

Like the other themes, Wallace litters examples of double binds throughout the book. We even get an explicit reference.

Enfield Tennis Academy

Students at the Enfield Tennis Academy, where half the book takes place, are required to keep up with their academic studies. One day they are literally tested on double-binds.

The test problem they’re given goes like this: Alice is a kleptomaniac (someone who wants to steal things) and an agoraphobe (someone who doesn't want to leave the house). What should Alice do?

One of the students tentatively suggests mail fraud.

This explicit reference reads like a joke you’d tell at a bar. But you start to realise that double binds form a large part of the book and, at least according to Wallace, a large part of life.

Later on we’re introduced to the authoritarian tennis coach Gerhardt Schtitt who’s around 70 years old but still in frighteningly good shape. He has some strongly held and unusual views on both tennis and life. He believes in hierarchy, competitiveness, and constraints. And he does not believe that a straight line is the shortest path between two points1.

Part of Schtitt’s coaching philosophy is that you shouldn’t care. This is hard to do. As Jerry from Rick and Morty complained when Mr Meeseks was advising on how to take two shots off his golf handicap.

Further, the reason you want to not care in the first place is because you do care about the result. Coach Schtitt explicitly wants players to simultaneously care and not care.

One of the tennis academy players, a minor character called Ted Schacht (coincidentally the only other character with a German name), has Crohn’s disease and a bad knee. Ever since he got injured he stopped caring about winning or losing which improved his game as a result. He seems to be the only one able to fulfill Schtitt’s coaching philosophy.

Ted Schacht was also an occasional drug user. The thing is, almost everyone in Infinite Jest is a drug user. As I noted previously:

Infinite Jest is filled to the brim with drug addicts. Affable addicts, athletic addicts, and abhorrent addicts. Current drug addicts, recovering drug addicts, and non-drug addicts who are addicted to something else.

Most drug usage in the book is pathological. However, Ted Schacht is not trying to escape anything. He is one of the few characters that has a healthy relationship to both drugs and tennis. Wallace is hinting that a potential way out of these double binds is somehow relinquishing any attachment to status or escape.

The main character, Hal Incandenza, is a tennis prodigy and genius savant. He notices a double bind around achievement: He recounts how his father was successful and exceeding all expectations but was ultimately unhappy. But his grandfather, who was a failure, was also unhappy. Perhaps similar to DFW’s struggle in writing great works.

Ennet House

Half of the book takes place at Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House2, a recovery centre down the hill from the tennis academy. Several double binds occur.

Many of the characters are drug addicts with conflicting higher order preferences. They want drugs but they also want to not want drugs. One character describes how in order to quit you need to admit you are powerless but being powerless means you can't quit. Another character says the problem with substance abuse is that you might die if you don’t quit but might lose your mind if you do.

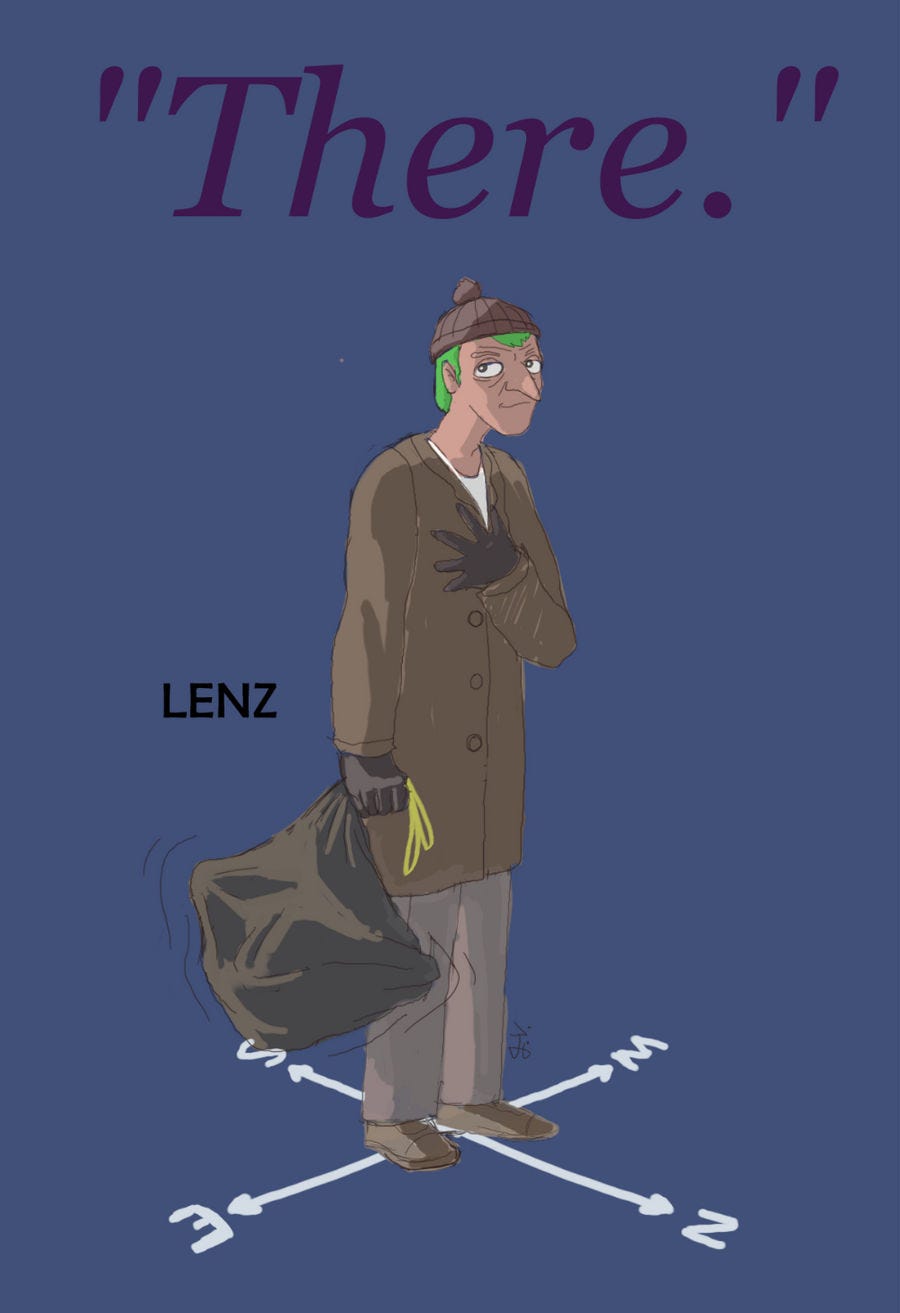

One of the patients is an unlikable man named Randy Lenz. He deals coke and is wanted by both sides of the law. He has several OCD tendencies such as constantly needing to be facing north. One of his compulsions causes a double bind: He needs to constantly know the time with exact precision but he also has an immense fear of timepieces.

One of his less redeeming habits is killing animals on his nighttime walks home from AA sessions. He starts by whacking rats with concrete slabs and upgrades to luring cats and dogs into trash bags. He cathartically says “there” to himself after each act. He befriends another patient who joins him on walks but is annoyed at the bind he finds himself in as he can’t kill animals anymore but also can’t blow him off as he’ll be misunderstood as to why he wants to be alone.

Near the start of the book we’re introduced to a future Ennet House patient Ken Erdedy who is stuck in several double binds. He’s planning one last massive weed binge. He's anxious because the girl buying weed for him is running late. He watches videos to distract himself but incessantly changes the channels in case there is something better on and ends up watching nothing. I get this feeling when starting 20 pages of a new book for the 5th time in a week.

He doesn't actually call the girl he’s waiting on because he wants to avoid blocking up the phone line in case she’s trying to call. He also doesn’t want to seem too keen and scare her off. The anxiety and claustrophobia of the scene slowly builds and finally culminates with Ken being paralyzed between the door intercom and the phone which both ring at the same time.

A somewhat cartoonish example of a double bind is a female character who is “stored” in a recovery unit nicknamed The Shed for “catatonic and vegetable-ish patients”. The woman is paranoid that she is paralyzed but also paranoid that she's blind. She refuses to ever open her eyes to test one of the ailments in case the other one is confirmed. She has become, for all intents and purposes, paralyzed (and blind).

Some of these examples are a bit silly or just DFW being clever. Yet the theme of double binds is intentional and deep. Life is full of these seemingly irreconcilable demands, both of which are unacceptable.

Because things get in the way.

With a footnote pointing out the redundant "house" in the title