Book Review: How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read

Sometimes you hear praise of book reviews that goes something like this: "This review did its job: it convinced me to purchase the book!".

This criterion has an obvious logic: The review successfully conveyed that a book was interesting enough to be worth the reader’s time.

An issue with this criterion, however, is that it rules out an indispensable genre: Good reviews of bad books. Stuart Ritchie's critical review of Cordelia Fine's Testosterone Rex and Steven Pinker's damaging review of Malcolm Gladwell's What the Dog Saw were informative and well written but didn't have me running to the bookstore. Andrew Gelman had a similar effect while reviewing Noise without even reading it.

Pierre Bayard, the author of How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, would approve. His book opens with an epigraph from Oscar Wilde: "I never read a book I must review, it prejudices you so".

A more important issue with the did-it-cause-you-to-buy-the-book criterion is that a review may be so good that it obviates the need to read the book itself. Even when the book is highly praised. If the review is insightful and intellectually honest, why spend 20 hours reading 500 pages?

We already know this. Indeed, this is one of the reasons we love good book reviews.

Sure, sex is great, but have you ever tried being notified that Scott Alexander has recently reviewed a book that has been on your to-read list for years?

According to Bayard, we needn't be embarrassed by this behavior. Quite the contrary. Don't let the tiny insignificant fact that we technically haven't read these books stop us. We should be talking about Fussellian Class, illegibility, Igon Values, and implausibly hungry judges even if we haven’t read the books.

The awkward thing for me, if Bayard's thesis is taken seriously, is the audience perhaps shouldn't bother reading this review.

With that in mind, I suppose I better provide a TL;DR:

TL;DR

We gain and add value by discussing thinkers and books we haven't read.

Doing so is a creative act.

An understanding of where a book sits in relation to other books and ideas can be as important as its content.

Even in the cases where we've completed a book, we don't know all the background context and we're in a constant state of forgetting.

Talking about books we haven’t read is something we do anyway. We should be less embarrassed by it.

I’m ambivalent on including this Blinkist styled overview that wouldn’t look out of place on a productivity guru’s twitter thread. Nabokov would advise against it. He argued that the general summary is the exact wrong end to understand a book. Rather, we must fondle its details to gain artistic appreciation. Bayard would remind us that many details can be accessed without reading.

Either way, I’ll include some details below.

Bayard's taxonomy

One reason we shouldn't worry ourselves with reading any particular book is that, in a sense, we haven't fully read any book. Even the ones we’ve read. Sure, our eyes may have looked over every word between the covers. More than once even. But we never understand a book completely from simply reading it.

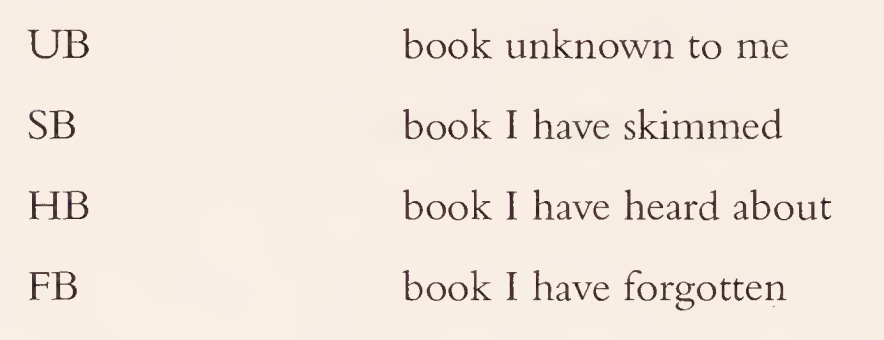

This paradoxical claim, which I’ll unpack shortly, explains Bayard's quirky classification system. Before he begins, he lists out abbreviations to classify books:

"Book I have read" is notably absent. This is the most important take home lesson about his system. We can’t draw a straight line between books we have read and books we haven’t.

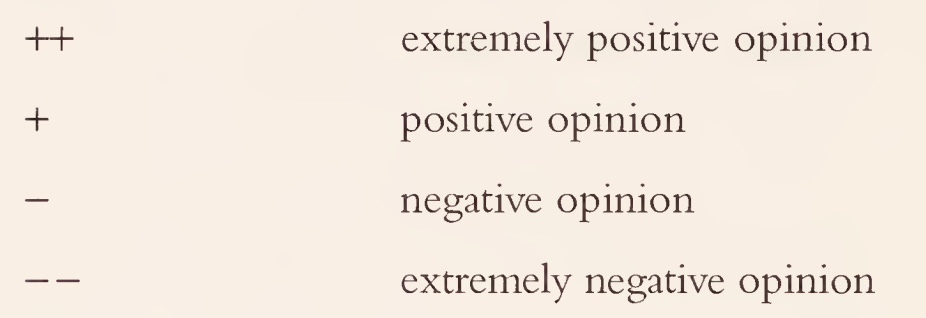

This doesn't stop him from rating books. His rating system includes the following:

This system makes explicit a process that many of us already do: We have opinions on books we haven't read. Think of your favorite ACX reviews. Or think of controversial books like Robin DeAngelo's White Fragility or Charles Murray's The Bell Curve1. We tend to have opinions.

In the spirit of Bayard, I'll follow his classification and rating system.

A tour of books you may not have read

Bayard uses each chapter to analyze a different book to support his claims. The irony of providing close readings of several books in the midst of telling us not to bother with reading will not be lost on him. Bayard comes across as self-aware, although it’s not always obvious how tongue-in-cheek he’s being.

Rather than an admonition of reading, Bayard’s book is best thought of as a love letter to literature. It’s an ode to our creative engagement with it in more ways than reading.

Be warned, when analyzing the different books he doesn’t avoid spoilers. Another warning is that some of his spoilers just ain’t so. For each book he references, he changes one plot point without mention and treats it as he does the rest of the analysis2.

For a rather trivial example, in his discussion of the ending of The Third Man, he unites the protagonist Rollo Martins with the girlfriend of Harry Lime. In the original text, she walks on by.

Bayard defends his meddling by arguing that these changes are what should have happened based on his interpretation of the book, and are as real to him as any other detail.

“To be sure, these facts are not directly stated in the texts. But like all the facts I have offered the reader, they correspond for me to what I see as the likely logic of each text and thus, as far as I’m concerned, are an integral part of them.”

Kind of like how Hermione is obviously a ravenclaw.

What do you mean I haven’t read any books?

Goodreads tells me I’m at 27 books for the year and counting. What is Bayard getting at when he says we haven’t fully read any book?

He argues that we never understand a book completely from simply reading it. Thus, setting the we-are-allowed-to-discuss-it threshold at whether we’ve read it is arbitrary. We haven’t learned where the book sits with other books. We don’t know its background influences. We don’t know its significance.

A book is not an isolated object: It's a part of a vast sea of knowledge.

Full understanding requires background context. Not only its direct influences, but other ideas that support or contradict the main thesis. It's impossible to have read every relevant book. As Taleb says in the Incerto3, the further into the ocean you swim, the more you appreciate its depth. Our anti-library is forever growing.

Counting a book as “read” by having turned 100% of the pages rather than 60% or 20% is wrongheaded. It’s like being an ethical vegetarian rather than a vegan: the threshold is symbolic. It sets us up as victims of Goodhart's Law. Our goal should be accretion of knowledge. Not pages read.

Voracious readers don’t tend to finish books. This may even be what it means to be a big reader. Many systematically skim as outlined in Adler’s classic How to Read a Book4. For instance, Marshall Mcluhan always skips the first 60 pages. Tyler Cowen finishes 10% of what he starts. Patrick Collison often skips ahead a few times before putting it down.

Bayard cites Valéry, who freely admits to systematically skimming Marcel Proust when writing criticism. Valéry instead chooses to seek passages that catch his attention:

“The interest of the book lies in each fragment. We can open the book wherever we choose.”

As Bayard says:

“The fertility of this mode of discovery markedly unsettles the difference between reading and nonreading, or even the idea of reading at all. ... It appears that most often, at least for the books that are central to our particular culture, our behavior inhabits some intermediate territory, to the point that it becomes difficult to judge whether we have read them or not.”

Forgotten Pages

Another reason we shouldn’t be concerned about finishing books is that we are in a constant state of forgetting what we've read. Most of it quickly metamorphoses into summary. Bayard states:

Reading is not just acquainting ourselves with a text or acquiring knowledge; it is also, from its first moments, an inevitable process of forgetting.

When making this point, Bayard cites the Essais5 where Montaigne, the ultimate man of reading, incessantly laments his terrible memory and prefers to describe himself as a “man of no retentiveness”.

Claiming we have read a book becomes a form of metonymy, Bayard points out. When discussing books, we are really discussing our approximate recollections of them.

As I’ve noted elsewhere: Most readers are familiar with the feeling when, after having finished a book we genuinely enjoyed, we go to tell someone about it and only remember a vague outline we could have gotten from Wikipedia. Maybe a detail or two.

Reminiscent of Woody Allen after reading War and Peace:

It’s about Russia.

This is fine if we were just seeking enjoyment. But it’s harder to justify this if the reason we picked up the large non-fiction tome was because we wanted to learn from it. Picking up the next tome shortly after forgetting the previous one resembles Sisyphus and the boulder.

This ubiquitous forgetting is why Andy Matuschak argues that books don't work6. However, he doesn’t think our memory is doomed. He’s a proponent of implementing a spaced repetition system as a strategy to help remember what we’ve read (i.e. making flashcard prompts for repeated reviews).

On our inexorable memory loss, Bayard is wrong. We aren’t condemned to a state of forgetting if we diligently implement this system. Although, even with the best systems, some of the book will still turn to oblivion. And it’s not like we all use these systems anyway. For most of us, at a descriptive level, Bayard is right: We forget what we read. He would also likely point out that we can gain many of the benefits of the system without actually reading all that many books but by talking about them.

Connections that count

This brings us to one of Bayard’s central points: Understanding a book's location is as important as understanding its content. By a book's location, he means knowing where it sits among other books and ideas. Which books influenced it? Which books make reference to it? Which books disagree?

When making this point, Bayard cites Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities7.

Bayard focuses on the librarian character who never has time to read any book. He only cares about organizing them and knowing their location.

“If you want to know how I know about every book here, I can tell you! Because I never read any of them.”

The librarian has encyclopedic knowledge of the interconnectedness of books yet has not read a single page.

We don’t have time to read every book worth reading let alone every book that exists. Even if we can Lex Friedman it and read one book per week that’s only around 2,600 in 50 years. To some extent, we have to focus on learning about books.

Fortunately, we can learn a lot about books without reading them. Bayard cites Joyce's Ulysses8 which most of us haven’t read. Yet we know about it. We know that it's a retelling of The Odyssey9. Heck, we probably haven’t read that either. We know that it's set in Ireland, it takes place over a single day, and it's written in stream of consciousness. We are able to talk sensibly about it. We also know how influential The Odyssey is on books in general.

Having a relational understanding goes beyond simply reading a book. It involves a comprehensive understanding of books as an interconnected system. It’s being able to place each one in its proper context.

Bayard's emphasis on relational understanding strikes at the heart of what it means to understand something. As Wittgenstein elegantly said in Philosophical Investigations10:

“A wheel that can be turned though nothing else moves with it, is not a part of the mechanism”

Understanding something means integrating new ideas with our existing knowledge. We can begin doing so without necessarily reading the content of a particular book.

For instance, let’s look at two university students, Alice and Bob. Let’s assume both are completely unfamiliar with Hegel. In their philosophy class, they are assigned a chapter from The Phenomenology of Spirit11.

Bob struggled through this chapter. He read it in isolation and didn’t do any other background research. Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to attend the tutorial discussion.

Alice, on the other hand, didn't read a word of Hegel (like most normal people). She instead read Wikipedia, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Singer’s Very Short Introduction12 and the relevant sections from Fukiyama’s End of History13. She learned that Hegel influenced Marx and annoyed Schopenhauer, both of who's work she was somewhat familiar with.

Alice then attended the tutorial and stayed after class discussing Hegel at length with her knowledgeable tutor.

Who better understands Hegel? Not necessarily the one who read him.

This is not to say that no value can be gained from Alice engaging with the primary source. It is simply to say that value can still be gained from not reading it. Greater value, in some cases.

(This example might not be completely fair as no one has read Hegel and has any idea what it is about.)

Bayard labels Alice’s process as active non-reading: a vital component to understanding any book. As the name implies, it is an active process. We can creatively engage with a book without actually reading it.

We can talk about Popper if we’ve read Deutsch. Korzybski if we’ve read Yudkowsky. Darwin if we’ve read Dawkins. Freud if we’ve read The Last Psychiatrist. Even if we’ve only talked to people who have read them.

The university example above may have been contrived, but this sort of thing happens all the time. My friend read Piketty's Capital last year. Took notes at the time and everything. He’s forgotten most of it apart from the sorts of things that can be gleaned in a blog post, like r > g.

Interestingly, another friend, who hadn’t read it, had better relational understanding on some points. For instance, he was aware of Piketty's huge whiff of ignoring depreciation. As was pointed out by the grad student Matthew Rognlie: The difference between r and g was due to land appreciation.

Our Inner Books

Bayard uses the term ‘inner book’ to describe all the influences of individuals and culture that shape our reading. There is no escaping our inner book and we are often not conscious of its pervasiveness.

Bayard’s inner book contains Freud and the French postmodernists Derrida and Lacan. The inner books for the readers of this blog likely contain the rationalist canon. Per Bayard:

In truth we never talk about a book unto itself; a whole set of books always enters the discussion through the portal of a single title, which serves as a temporary symbol for a complete conception of culture. In every such discussion, our inner libraries — built within us over the years and housing all our secret books — come into contact with the inner libraries of others, potentially provoking all manner of friction and conflict.

Our inner libraries form us and mediate how we interact with new books. This echoes William Gibson’s notion of personal microculture. Or as Bayard puts it:

For we are more than simple shelters for our inner libraries; we are the sum of these accumulated books. Little by little, these books have made us who we are, and they cannot be separated from us without causing us suffering.

Many books and ideas contribute to an egregore which we engage with whether we’ve read them or not. There are risks associated with this that I outline in a later section. However, it’s somewhat unavoidable and engagement of this type still requires genuine creativity.

Creativity

Bayard argues that discussing books we haven’t read is “an authentic creative activity”. Learning is an active process from the learner. Thus, Bayard aptly described his recommended activity as active non-reading.

This is perhaps Bayard’s main purpose: To encourage creativity. Active non-reading is the only way to keep our heads above water. As he notes:

Non-reading is not just the absence of reading. It is a genuine activity, one that consists of adopting a stance in relation to the immense tide of books that protects you from drowning. On that basis, it deserves to be defended and even taught.

It’s not only creative but collaborative. When we talk about books instead of reading them there is another party: our conversation partner. A book is not an isolated object: We can learn from other people. Conversation also gives us immediate feedback.

Successful active-nonreading presupposes that it’s possible to engage with and understand a book without reading it. On this point he cites Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose14.

The protagonist, English detective Baskerville (an homage to Sherlock Holmes), figures out the mystery without fully reading the pivotal item at the center of it: Aristotle’s Poetics15. He does this in part by engaging with others’ reactions to the text.

Bayard makes the point that learning is an active process from another angle: No two people have the same understanding of a book. Reading a book does not directly transmit its knowledge to the reader like pouring water into a vessel. Karl Popper in Objective Knowledge16 calls this misconception the bucket theory of knowledge. The reader creates meaning.

In The Name of the Rose, the monk Jorge from Burgos (an homage to Jorge Luis Borges) interprets Poetics as at odds with faith because Aristotle’s legitimization of laughter turns anything into an object of derision. Baskerville disagrees. But, importantly, he is able to engage with it in part based on the monk’s reaction to it. Discussions allow access to books without reading them.

Bayard also cites Oscar Wilde’s notes on criticism to discuss creative non-reading. Bayard notes that the book itself is a mere pretext. It is to stimulate creativity in us. To inspire us to write, discuss and learn. Reading is far from the most important aspect.

Hence the opening epigraph: “I never read a book I must review, it prejudices you so".

This quote was actually misattributed to Wilde in Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading17. Bayard buries this caveat in a footnote later in the book. Funnily enough, when we now search this quote, google attributes it to Wilde due to the success of Bayard’s book.

Similar to his meddling with plot points, Bayard claims that in a sense this quote is Wilde’s. It certainly feels Wildeian and we could imagine him saying it. Kind of like Voltaire’s: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it" which is as Voltairian as it gets. Or Sherlock Holmes’s “Elementary, my dear Watson”.

Like Bayard’s added plot points, he views these quotes as authentic. Our culture has manifested them.

This is a little post-modern for my taste. I agree that quote is Voltairian but we shouldn’t ignore the fact it wasn’t literally said by him. There’s value in keeping one foot moored to reality. Although it does feel a little pompous having to insert “oft-misattributed to” after all Mark Twain quotes.

Shame

Even though discussing books that we haven't read is a near-universal behavior, we feel ashamed of it.

School infuses this shame by emphasizing reading from the first page to the last. Sometimes the onerous task of reading difficult books turns us off reading altogether. Many have wounds from giving up books we “should” read: Our unfinished copies of Infinite Jest18 look as tired as we did reading them.

We lie about the way we read and what we’ve read. Our lies tend to be proportionate to the perceived significance of the book.

We also lie to ourselves. We view ourselves as having read books that we may have skimmed and that we have certainly forgotten. As Robert Trivers' work on self-deception showed: Deceiving ourselves makes it easier to deceive others. This assuages our guilt for talking about books we haven’t read.

“I know few areas of private life, with the exception of finance and sex, in which it’s as difficult to obtain accurate information,”.

Bayard seems to endorse our lies. By raising the status of non-reading, Bayard wants us to genuinely stop feeling guilty. Although he doesn’t expect us to start including caveats in our essays like “I’ve partly read Moby Dick a few times before giving up”. He’s fine with us to continue allusions implying that we’ve read it. He thinks we’re all sort of in on it anyway.

I view lying as less of a benign act as Bayard. Anne Frank hiding in your basement aside, we should tell the truth. Although I agree with Bayard that there is often no clear line with reading vs not-reading.

He includes a humorous practical tip: If you ever find yourself talking to an author about their book you haven’t read (a scenario that a French literary theorist probably finds himself in far more than us), we should be overwhelmingly positive: “Praise it without going into detail.”

He cites Rollo Martins, the American adventure novelist visiting Austria, in Graham Greene’s The Third Man who is mistaken for another author that shares the last name Martins. Rollo successfully responds to literary critics questions on books in the Western Canon which he very much has not read.

Dangers of Reading

Bayard reminds us that it’s important to stop reading at some point. Not only due to the opportunity cost in time, but because it’s hard to hear our own voice. Original thoughts require solitude. Something we all find difficult as evidenced by the fact we prefer to shock ourselves than sit in a room being bored.

When we read, our default is to let the author do the thinking for us. Schopenhauer, in Essays and Aphorisms19, said we can “read ourselves stupid”:

When we read, someone else thinks for us: we merely repeat his mental process. … It stems from this that whoever reads very much and almost the whole day, but in between recovers by thoughtless pastime, gradually loses the ability to think on his own – as someone who always rides forgets in the end how to walk.

At some point we must stop reading. We must consciously engage with our own thoughts. Whether that be solitary thinking or discussion with others. Writing is another way to understand what you think. This active non-reading activity sharpens our ideas. Don’t forget to also write about books you haven’t read.

Dangers of Not Reading

Bayard's doesn’t mention risks. One assumes they don’t exist in Bayard’s world. One obvious problem in talking about books we haven’t read is that we are far more prone to misrepresenting an author’s ideas if we skip the ‘reading them’ part.

It’s common for authors to complain about critics missing the point from obviously not reading the book. Richard Dawkins wonders if many critics got past the provocative title when reviewing The Selfish Gene20. The phrase “selfish gene” may easily mislead if someone skips the “large footnote of the book itself”.

Oliver Traldi outlines this in Nobody Reads: We risk misrepresentation. Although he makes many similar points to Bayard: He concedes that people who haven’t read a book may know more about it than those who have not. He admits that he talks about numerous books he hasn’t read. And he claims that we’re often on safer grounds discussing books we’ve read about than those we’ve read. Bayardian indeed.

But the risk of misrepresentation and misunderstanding is real. Along with all the warped incentives in academia, one of the reasons that a lot of science is fake is because people simply don’t read the studies. Citations don’t correlate with replicability. One wonders if they correlate with having been read.

My feeling is Bayard would reject the criticism of increased risk of misrepresentation. Although he doesn’t explicitly address it. He offers this sort of relativistic notion that all interpretations are equally valid, whether or not we’ve read the book. Hence his intentionally-incorrect recounts of part of the novels. If so, this is where he and I part ways. It is possible to misrepresent an author, and it is bad for cultural discourse.

Another issue is that a book’s reputation influences our perception of it. Bayard makes this point, and thinks this is why it’s important to non-read. For him, the cultural osmosis of the book is far more important than the book itself. But this can make it hard to form your own opinion. It’s kind of like how everyone ignores the fact that they found There Will Be Blood boring when they watched it as a 16 year old aspiring filmy because it’s the best film of the decade. Or that indie music fan who doesn’t like rap but feels like he needs to earn his open-minded bonafides so he gives it a whirl. He goes straight for Nas’s acclaimed Illmatic. Whether he likes it or not, he’s going to write a banal summary on RateYourMusic with a few caveats that “hip hop isn’t really my thing but it was really impressive” and then give it 4-5 stars.

This sets me up nicely to inform you that some impressive people endorse How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read. Umberto Eco loves it. Venkatesh Rao lists it as his number one book on Ribbonfarm. So feel free to rank it up there with Paul Thomas Anderson and Nas.

Conclusion

Bayard is a little postmodern at times and he underrates some risks but his main argument is ultimately correct: We can talk about books we haven’t read and doing so is a valuable and creative act.

The title may sound like you’re signing up for a productivity hack but Bayard is erudite, deep, and his light-hearted approach and constant wit makes for a pleasant read.

I won’t make the obvious joke that I didn’t read this book as it’s not true. However, I happily endorse any reading or non-reading of this book.

The Straussian in me will refrain from rating these books.

In fact, David Lodge wrote to Bayard pointing out that he got a plot point wrong in Lodge’s Small World. Bayard would have chuckled: Like all good non-readers, Lodge must have skipped the bit where Bayard explains he makes changes.

SB+

SB++

SB++

FB++

HB++

HB++

HB++

HB+

HB-

FB+

SB++

FB+

HB++

SB++

HB+

FB++

SB++

FB++

I'm a little surprised how therapeutic reading this was. I really needed somebody to give me a good reason to not stress about all the important non-fiction that I haven't read - I probably already have gotten the most important ideas from the most influental books already. The main stress-reducing idea I got from this is treating reading non-fiction books like verifying the information in the primary source. I'm definitely going to appreciate second-hand information about books, like book reviews, even more than I did before. I really appreciate you having done this review about Bayard's book (HB++)

Thank you for this review! Without really thinking about it (except to occasionally feel guilty that I'm acting like I've read a book I haven't) I've long approached reading from this perspective. There are a great deal of authors I understand well from hearing them referenced over and over, and on the flip side, many primary sources I read and would have been lost in if not for some kind soul's background and annotations. Sometimes I feel nihilistic, pondering the immense mass of books around me that I'll never reach – and why should I ever want to contribute, when there's far more worthwhile things than I could ever produce? – but viewing the world of books (and blogs, etc.) as a conversation greater than each individual tome is both more heartening and, I think, truer. For one example of collaborative reading: recently I saw a deeply annoying and poorly written book getting praised to Heaven and back on Twitter. I immediately knew the leftist tradition the author was coming from, and had in fact met a person or two like him before. I tried reading the book and couldn't get more than a few pages in, the writing was so bad, but I told my girlfriend and she read the whole thing. She took notes and told me about it and we wrote a review together. Through her notes I identified the pop science the author had engaged with (on the most surface of surface levels) because I had seen that pop science, and the misinterpretations, thereof. It was the most I've ever read a book without reading it, though the shallowness helped. A lot.